Creating inclusive classrooms

Exploring key concepts of DEIB with practical steps to cultivate a supportive and equitable learning space.

In today's diverse society, fostering an inclusive classroom environment is vital. By embracing the principles of diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging (DEIB), we can create a space where every student feels valued, respected, and empowered to succeed.

Understanding DEIB

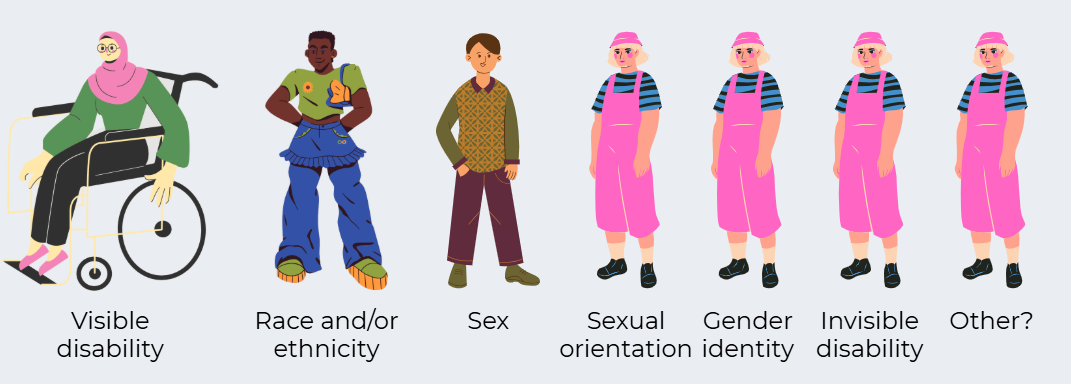

Diversity refers to the differences among people, encompassing visible traits like race, as well as hidden aspects such as gender identity, neurodivergence, or cultural backgrounds. Recognising and valuing these differences is the first step towards creating an inclusive environment.

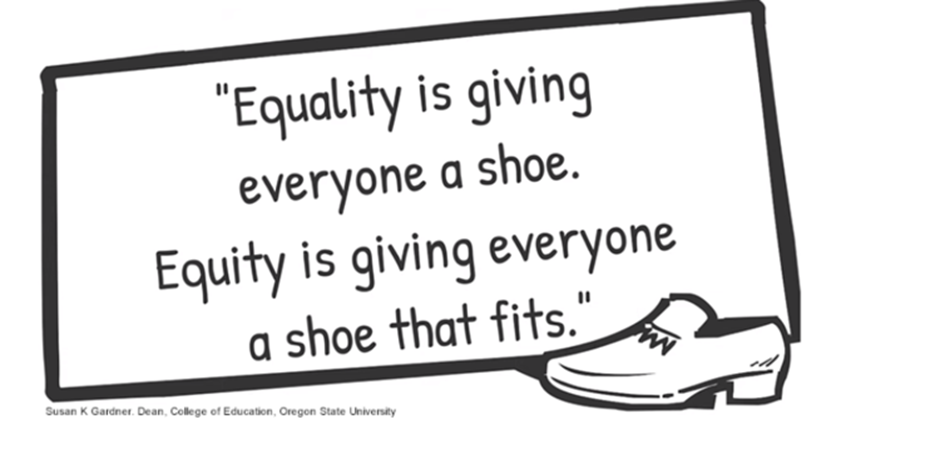

Equity and equality are often used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings. Equality involves treating everyone the same and providing identical resources. In contrast, equity acknowledges that individuals have different needs and starting points and accommodates these accordingly.

Inclusion is the active process of ensuring that diverse individuals are respected, involved, and celebrated. When equity is practised, inclusion follows.

Belonging, the ultimate goal, is achieved when individuals feel at home and safe to be their authentic selves without fear of judgment or exclusion.

Strategies for Promoting Inclusion and Belonging

A culturally connected classroom acknowledges the multiple identities in the room. It is an actively constructed entity designed to create cohesion and understanding. It is a conscious space in which students are made aware of difference and similarity, equity and respect.

Bennie Kara, A Little Guide for Teachers: Diversity in Schools (Sage Education, 2020)

Psychological Safety

A cornerstone of inclusive classrooms is psychological safety, where students feel secure to express themselves, make mistakes, and engage in open dialogue. We can model vulnerability by sharing our own learning journeys and mistakes, fostering an environment where errors are seen as learning opportunities to embrace, rather than a source of embarrassment.

Encouraging Healthy Dialogue

In an inclusive classroom environment, students should feel comfortable disagreeing and challenging ideas. Teachers can promote this by modelling respectful dialogue and establishing clear boundaries that support healthy interactions.

Recognising Invisible Diversity

Many aspects of a person’s identity, such as sexual orientation, gender identity, neurodivergence, or mental health issues are not immediately visible. We should be mindful of these invisible diversities and understand that students may struggle with undisclosed or undiagnosed conditions. Examples of other aspects of identity could include Gypsy Roma Traveller (GRT) families, young carers, English as an additional language, looked after children, or a possible multitude of other characteristics that may prevent someone from fully accessing learning.

Understanding intersectionality

Intersectionality1 is a framework for understanding how identity is made up of unique combinations of discrimination and privilege. An example we might see in the classroom is undiagnosed ADHD in girls because a) it presents differently in girls from in boys; and b) girls are taught to mask inconvenient feelings and behaviour at a young age. Here, gender and neurodivergence intersect to add a layer of difficulty over and above simply having ADHD.

In addition, we need to consider that children who already feel vulnerable due to one aspect of their identity may not wish to make themselves even more vulnerable by disclosing another: for example, a Black child may feel extra reluctant to disclose that they are a young carer.

Identity isn’t fixed and can change over time, or suddenly. A previously seemingly happy and well-adjusted student may develop a serious mental illness. A pupil may become disabled after an accident. Their family circumstances may change suddenly. And teachers should remember that changes such as these will come with uncertainty and a degree of trauma that may well manifest in the classroom.

Therefore, a truly inclusive classroom and/or community must be able to both accommodate unseen need and also anticipate future need as much as possible.

Practical Steps for Inclusivity

Simple practices like creating an uncluttered environment, using clear audio-visual content, and providing both written and verbal instructions can significantly enhance accessibility. In general, clear instructions delivered in a calm classroom in multiple formats will help the accessibility of your classroom even if you don’t know every pupil’s needs.

Seating plans

Research indicates that students tend to sit with those who they perceive to be like them, often forming racial or ethnic clusters. By thoughtfully designing seating plans that mix different groups, educators can discourage unconscious. Avoid gendered seating that may create issues if a child identifies – openly or otherwise – as a different gender or indeed as no gender (Kara, 2020). Degendering the classroom as much as possible will benefit these students without needing to be explicit about it.

Speaking of gender, research shows us that in cross-sex two-party conversations – so, a man and woman talking to each other – men accounted for 96% of interruptions and 100% of overlaps (starting to talk before the other has finished). It’s worth thinking about how confident you are encouraging female voices in your classroom.

Use strategies like carefully chosen talk partners and the chip strategy to ensure all students have equal opportunities to contribute to discussions. Highlight the importance of listening and respecting everyone's voice.

Language and Terminology

Teachers should be cautious with language, avoiding phrases that may unintentionally stigmatise mental health issues or other disabilities. Use inclusive language that respects all identities and experiences.

Developing a shared language to discuss diversity demystifies it and facilitates open conversations. By being confident in the language of diversity we have a mechanism to discuss it. We should stay informed about evolving terminology, such as the nuances between race and ethnicity, and be mindful of how language can either support or harm inclusivity efforts.

Considering Identity

We can also reflect on our own identities and how to present ourselves in the classroom. While sharing personal experiences can promote diversity appreciation, teachers should balance this with maintaining personal and professional boundaries. We also need to consider wider societal issues and how students may interact with them – for example, the current discourse around LGBTQ+ identities, migration, or women’s reproductive rights. We don’t know what parent and carer attitudes are, or what children see and hear outside our classroom, and we need to be sensitive to this.

Conclusion

Creating an inclusive classroom is an ongoing journey that requires commitment, empathy, and intentionality. By understanding and implementing DEIB principles, educators can nurture an environment where every student feels a sense of belonging and is empowered to reach their full potential.

1The term intersectionality was coined by Kimberle Crenshaw in 1989.

You can access sources and further reading here.

Susi Waters is Operations Manager at the Julian Teaching School Hub and Norfolk Research School, based at Notre Dame High School (NDHS). As part of her role, Susi has developed and delivered training on Trans Awareness in the Workplace, Wellbeing and Managing Exam Stress, and DEI in the Teaching Workforce. She is also the DEI link between the Research Schools Network and the Education Endowment Foundation for the East of England and East Midlands Region and has previously been part of the Research Schools Network’s Developing Diverse Voices focus group. Outside of her core role, Susi has supported NDHS as staff wellbeing coordinator and has undertaken extensive training including Mental Health First Aid. Susi has previously worked in university outreach and events management.